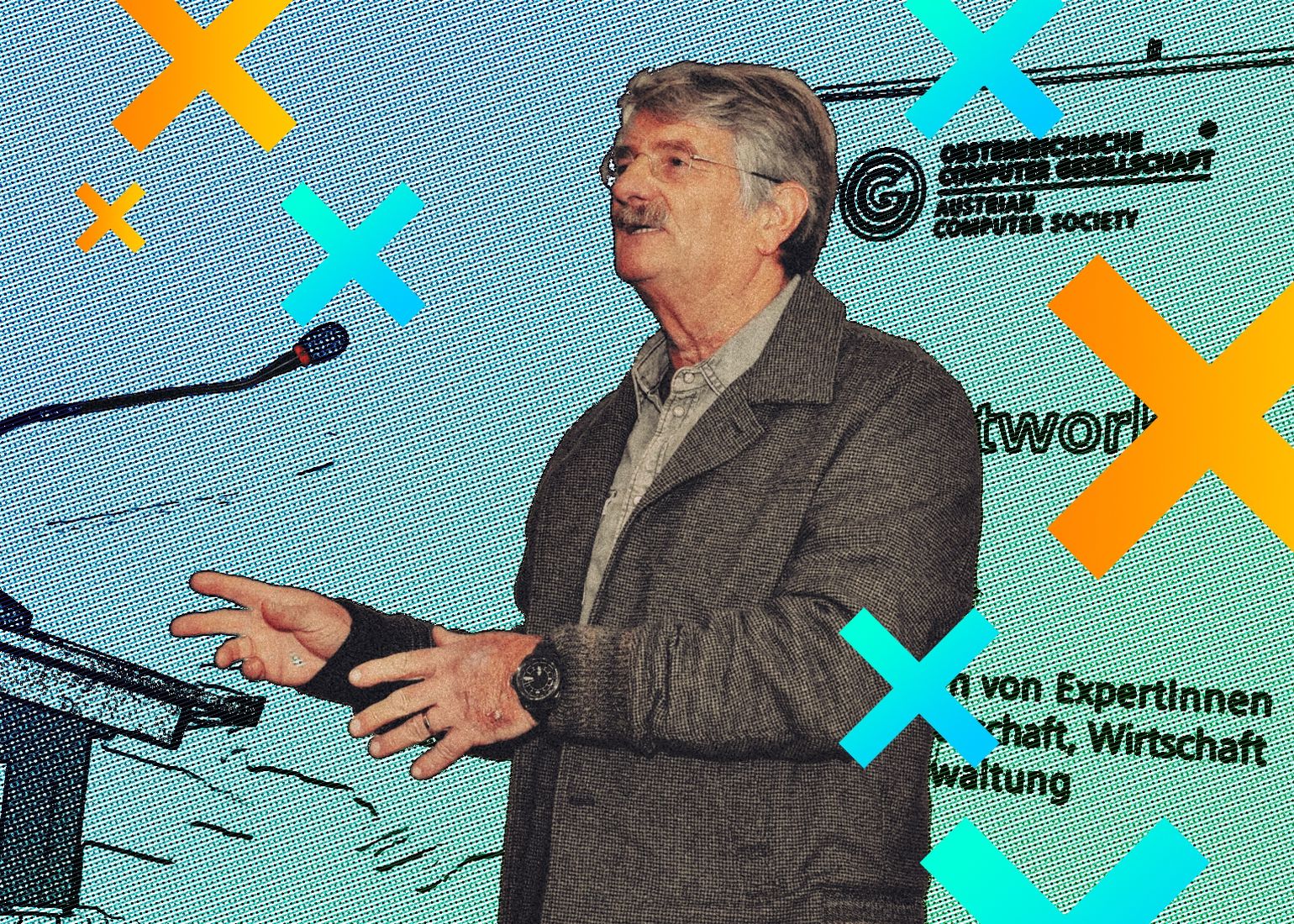

Oh, Javaman. A Tribute to Helmut Schauer

Helmut Schauer loves Bob Dylan’s Jokerman, but is definitely a Javaman. On December 2nd, he received TU Wien’s Golden Dissertation Diploma – 50 years after his graduation.

Picture: R. Handl / timeline / OCG; Design: TU Wien Informatics

First off, the ones of you who haven’t heard the song “Jokerman” by Bob Dylan should definitely check it out – for the sake of art, and for the sake of this article. Second off, when retelling the life of a highly accomplished person, it is easy to fall into a trap: Milestones, accolades, and awards that trace an extraordinary career are overwhelmingly many, but often miss all the fun, sad, exhausting, and honest stories that make up a life’s journey. Another narration of his CV is definitely not what Helmut Schauer, famous Professor of Informatics and infamous storyteller, needs – you can look that up on many different sites online, even on Wikipedia. This tribute is an attempt to weave Helmut’s stories into one of his favorite songs. So put on some Bob Dylan, and join us for the ride.

Jokerman dance to the nightingale tune

How many nightingales sang in Vienna’s 16th district when Helmut Schauer was young remains to be unknown, but dancing tunes, well, there were plenty. At the end of the 1950s, Helmut attended high school in Ottakring and discovered pop & rock music, first and foremost Elvis Presley. This very first step leading to his career in higher education was a close call – almost failing his high school’s entrance exam due to allegedly poor German grammar, he was only ‘conditionally’ accepted because his parents lived close by.

Picture: icce.rug.nl

How much time indeed went into perfecting his grammar skills from that point on is most uncertain, as the music lover’s sleepless nights were dedicated to his favorite radio programs. At that time, Radio Luxembourg (now RTL) had all the tunes you were waiting for, but the reception in Vienna was not ideal. No problem for Helmut, who had a knack for crafting and started to build his own shortwave receiver. To the great joy of his friends, receiving many tape recordings Helmut brought along for school and skiing trips. When his schoolmates started a band, he began to build tube amplifiers for their concerts. “I regret that I never learned an instrument myself,” he says looking back, “but while my friends played, I crafted.” With a high school diploma in his pocket and great freedom ahead, Helmut wanted to learn how the machines he built truly worked. Alas, things turned out differently.

Freedom just around the corner for you

In 1961, Helmut committed one of the greatest fallacies of his life. According to him at least. He enrolled in electrical engineering at TU Wien, presuming he’ll get to know the inner workings of machines and how to plan and build them. His disappointment was huge when he went to his first lecture at the low-voltage branch of the then Faculty for Engineering. Sitting in the first overcrowded lecture of many to come, he learned only one thing: Electrical engineering, like he imagined it, was an advanced course. Before even thinking about attending lectures, he had to learn what was termed ‘basic knowledge’ at TU Wien: Maths and some more maths, theoretical physics, and mechanics.

Picture: TU Wien Archive / Heinz Zemanek Estate

Picture: Helmut Schauer

Picture: Helmut Schauer

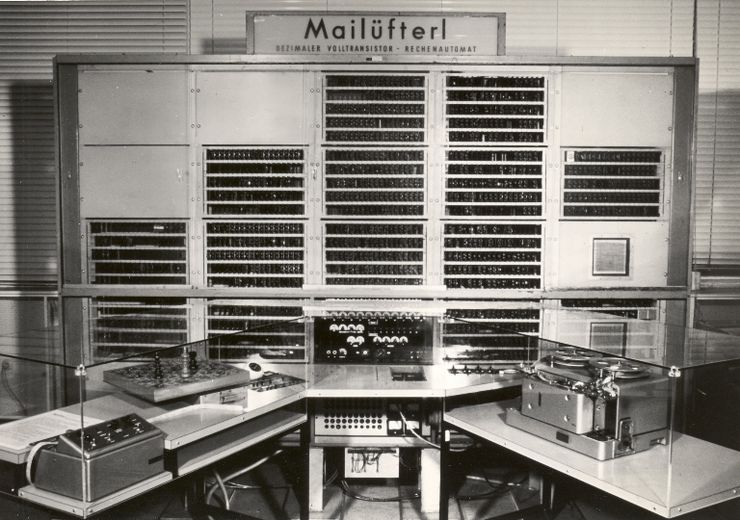

Yet, a wind of change was blowing at TU Wien, setting young Helmut on a different track. The involved wind machine was no other than Heinz Zemanek’s famous Mailüfterl, the first computer in Europe to operate entirely with transistors. Zemanek’s lectures fascinated the engineering student so much that he shifted his focus to programming. “Zemanek was a great storyteller, and in his lectures, all he did was tell stories about the Mailüfterl. There was more in this world than my shortwave receivers, and of course, I wanted to find out how computers work.” Thus, Helmut Schauer was the first graduate in electrical engineering who didn’t build any machine for his diploma – his whole thesis was programmed.

At that time, Professor Hans Stetter at the Institute for Numerical Mathematics received the IBM 7040 computer, the biggest transistor computer in the German-speaking world. Helmut started to attend his lectures and soon found himself in a peculiar position. Stetter’s assistant Werner Baron had difficulty introducing the students to Assembler and machine language. “His lectures were notorious for being incomprehensible, and people were getting irritated”, Helmut remembers, “but somehow, I made sense of it.” To the great relief of Werner Baron, who now could not only prove to Stetter that his lectures were not as unintelligible as rumors suggested but also found a new research partner.

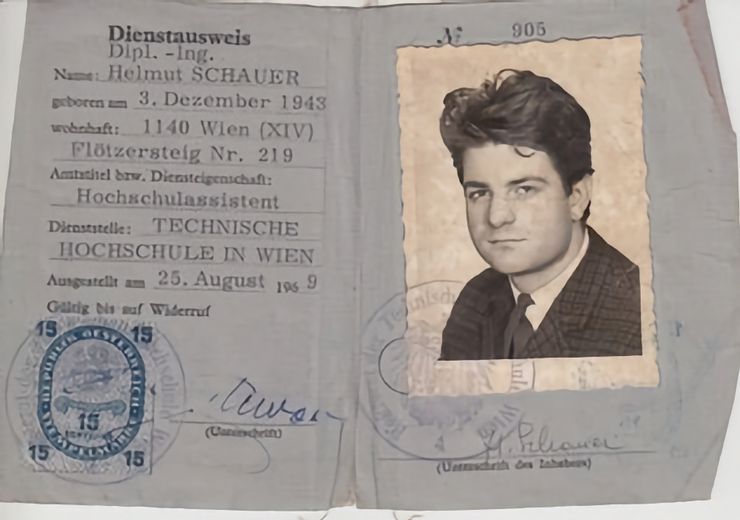

While still a student, Helmut was hired as a scientific assistant for machine programming. From handling punch cards to deciphering IBM magnetic tapes with indecent poetry, he excelled. After Hans Stetter went on a sabbatical to the U.S. for a year, Helmut gladly took over and held his first lectures in programming. Finally, in 1970, informatics was officially introduced as a degree program at TU Wien, and Helmut earned his doctorate two years later.

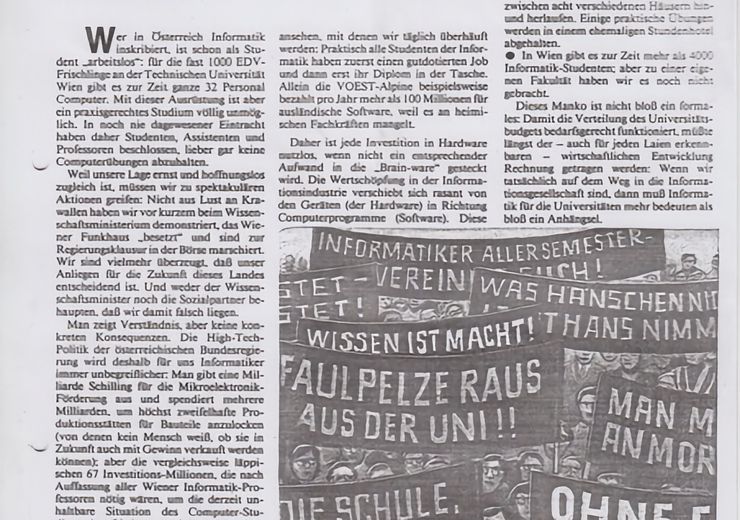

Nightsticks and water cannons, tear gas, padlocks

Viennese police didn’t go as far as tear gas, but when Helmut Schauer worked at TU Wien in the 1980s, the stakes were high. Informatics students and teachers were fighting for resources. “We needed computers and had none. We needed rooms but had nowhere to go. And we needed more people in informatics but were scarcely funded,” Schauer recalls the dire circumstances. Already appointed professor in 1986, he was also lecturer of the introductory classes in informatics with over a thousand participants. Helmut encouraged students and representatives of the “Fachschaft Informatik” to take action. And take action they did, leading to weekly demonstrations and the occupation of the Porrhaus (now Campus Treitlstraße, then owned by the Austrian Union ÖGB) and the Funkhaus Argentinierstraße, City HQ of the Austrian Broadcasting Cooperation (ORF).

“What the students didn’t know is that I always tried to negotiate with the police. The occupations were on a knife’s edge, with the police always ready to execute their power. So, I went over to the riot vans to cut some deals,” Helmut grins. During the Funkhausbesetzung, the police’s greatest fear was that the students would start live broadcasting from the station, but Helmut had a different set-up in mind: He got together with the journalists, and they unleashed a vast media coverage on underfunded universities.

“It wasn’t easy to keep so many young people in check,” he recalls, “at a demo during a government meeting at the Vienna stock exchange, students tried to cross the no-protest zone shouting ‘We’re just going to buy some stocks’. That could have easily blown up in our faces.” Still, the demonstrations remained peaceful, and success was not long in coming – in 1986, the Porrhaus was fully assigned to informatics, and new professorships and appointments followed.

Helmut’s social responsibility was not confined to the university. In 1984, when thousands of people occupied the Stopfenreuther Au to prevent the construction of the Hainburg-Danube Power Plant, he went there with his students to hold a widely acclaimed lecture on the technician’s responsibility for society. Despite wintry cold and several eviction attempts, the occupants persevered and saved the present Nationalpark Donau-Auen. Helmut Schauer started several citizens’ initiatives in his life – among them against a road construction project at Flötzersteig, which confronted him with a house search and suspicions of espionage; the construction project at Steinhofgründe, where the famous psychiatric ward and green belt should have given way to apartment blocks; an initiative against waste combustion and as a proud dog-owner himself, a life-long engagement for dogs and their rescue.

Bird fly high by the light of the moon

By moonlight or daylight, flying or on rails – the many kilometers that Helmut Schauer traveled between Switzerland and Austria after taking up his professorship at the University of Zurich in 1988 remain uncounted. Every weekend for 20 years, he commuted between Zurich and Vienna, soon getting to know the car conductors on the night train by heart. Personal encounters were plenty on planes & trains, “the most peculiar incident I remember was a young couple riding with me in the sleeper. They switched coaches for a very special moment, but little did they know that the compartment was to be disconnected – so they got stranded without clothes in Bischofshofen, in winter”, Helmut laughs. With his wife, daughters, and many dogs still in Vienna, “accepting the professorship in Zurich didn’t feel like a farewell. I am grateful that my wife supported me in this decision, enabling me to discover academia anew.”

Picture: Helmut Schauer

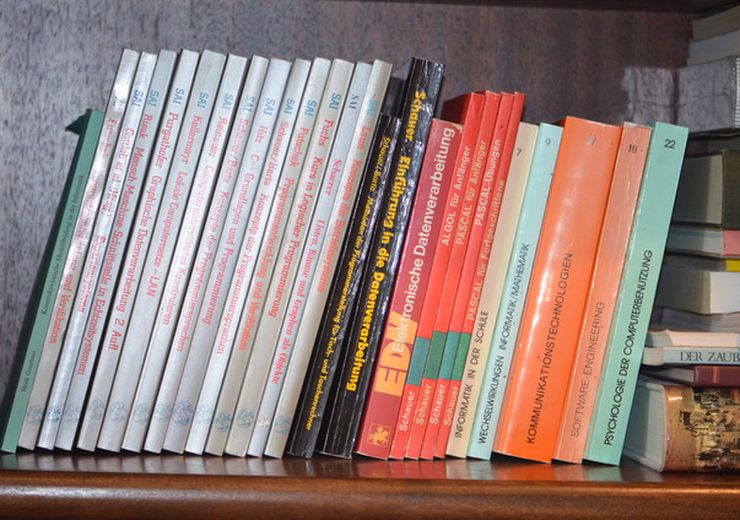

Because one thing truly set the post in Zurich aside: Finally, resources were not something to fight for, but something to use. As head of the Educational Engineering Lab, Helmut was able to fully immerse himself in his research and hire what he termed “a chaotic group of exceptional talents.” He worked with programming languages (PASCAL, LOGO, Java), web- & game-based learning, collaborative learning environments, and visualization of algorithms & data structures.

Picture: Helmut Schauer

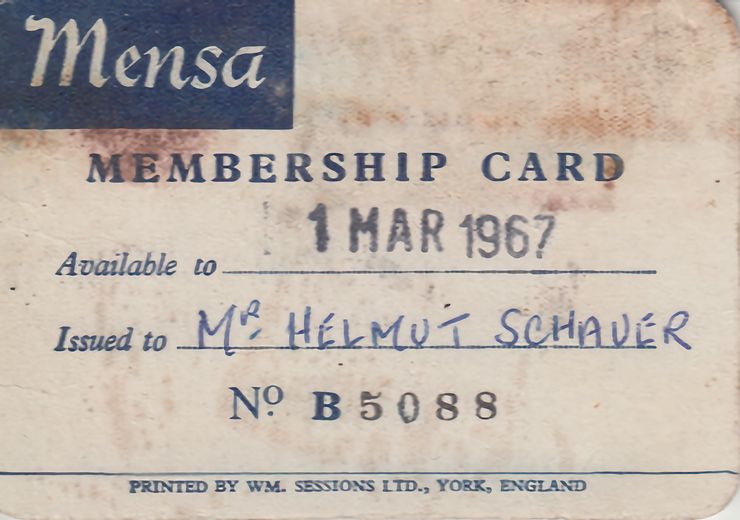

Being called the “Pope of PASCAL” in Vienna after his book “PASCAL für Anfänger” (PASCAL for beginners) was a huge commercial success (leading to some fame and a small sailboat), he now focused on Java. Adele Goldberg, one of the first developers of object-oriented programming languages, was a close friend, and further convinced him of the innovative new languages. Not long after, he was known as the “Javaman”, using Java as his main language for teaching and developing – thereby shaping a whole generation of computer scientists. “Languages shape the way you think, and the same goes for programming languages. I am still convinced that you have to start with object-oriented programming because it gets increasingly hard to grasp it in later stages,” the Javaman is sure.

Manipulator of crowds, you’re a dream twister

Teaching turned out to be more than just a profession for Helmut, it was a calling. He shaped and introduced informatics teacher education for all of Switzerland, in four languages. Through his communications skills, he had many connections to the industry, recognizing the value of informatics school education. First and foremost, the Hasler Stiftung, sponsored by the famous telegraph engineer Gustav Hasler. When the need for telegraphs plummeted, Hasler Werke invested in future information technology and generated a fortune they re-invested in informatics research and education. “When informatics was introduced as a diploma subject at schools, it went amiss – there were no teachers. The Hasler Stiftung supported us with vast sums to develop a center for teacher education,” Helmut recalls.

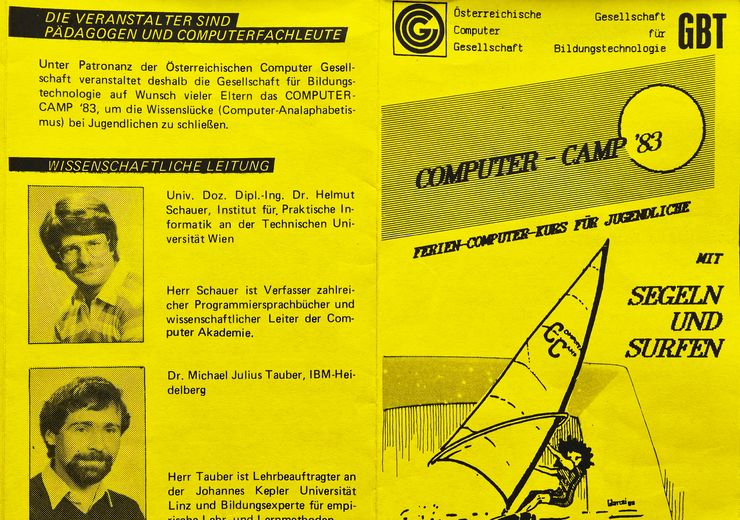

You didn’t dream about being in informatics when you were young? Well, that’s where Helmut comes in. He and his former student and colleague Gerald Futschek, retired professor at TU Wien Informatics and founder of the eduLAB and others, organized countless informatics camps and education initiatives. The first step is always to get people interested, “and that’s not something you do with theory, but with fun. Make figurines dance, program robots, and you get a small but instant sense of achievement. There are endless possibilities,” he is convinced.

Helmut’s computer camps were open to everybody – rich, poor, gifted, average, boys and girls. “We had a child at a camp that forgot to eat because computers were just so fascinating to them. Luckily we noticed soon enough,” Schauer remembers laughing.

Supporting women and marginalized groups in informatics is highly important to him. “Not only once was I confronted with reproachful questions as to why my university assistants were taking so long for their degrees. Well, in my group, many members were taking their parents’ leave. I am convinced that an academic career must be compatible with raising a family.” For many years, Helmut was part of the equality commission at the University of Zurich, as the only male faculty representative. “The appreciative communication within the commission lead us to many achievements. I unfortunately cannot say that this is true for the most male dominated groups I worked with.”

The law of the jungle and the sea are your only teachers

Working in informatics means learning something new every day. If we compare the development of tech in the last decades with what is relevant today, we see that specific knowledge has a shelf-life of only a few years at the most. But like nature has its laws – the sea has its currents and waves, the jungle has its specific micro-climate and soil structure – there are fundamental principles in informatics that are forever valid. “For me, modeling, notation, recursion, structures and relations, formalized systems, and their specifications are the core concepts of informatics. It is illusory to believe that computer science will ever teach the current state of technology. Technological change is happening too quickly and the system is too sluggish in comparison. Contrary to what you might think, this is a good thing. Teaching should primarily be about concepts that are valid in the long term and not about fads and coincidences,” Helmut Schauer is sure.

For a long time, Helmut believed that digital natives will have a vastly different approach to informatics because they can already use computers and can’t be deceived that easily. But that might not be completely true. According to him, we’re living in an age of polarization. Technology deniers wanting to recede to the dark ages, being proud that they don’t use the Internet or don’t have a smartphone – “I think that’s stupid, " Helmut states. “It is certainly problematic if all you do is cradle your smartphone, but total denial is just as foolish. We need to find the middle ground and take advantage of both worlds. Remote work and virtual learning are two fundamental pillars of this development, which I have propagated for decades.”

His advice to youngsters venturing into informatics is to demand more diversity and freedom for learning. Of course, core principles have to be part of the curriculum, but one has to consider different approaches to teaching them. “The pandemic has shown us, that there are many ways to work and learn, which are not bound to time and space. We should use these new possibilities – you see things on screen better anyway,” Helmut grins. “My recommendation to new informatics’ students: be curious. Within and beyond informatics. Not all knowledge that you need can be found in computer science. Enroll in a second subject if possible, go abroad, be creative and daring,” Helmut Schauer suggests. To put it in Bob Dylan’s words, and Helmut’s favorite quote – at school, at work, and beyond, always ask: what else can you show me?