A2RL Season2: Team Flyby snatches Silver Medal!

We’re excited to announce that team FlyBy snatched a silver medal in the second season of the Abu Dhabi Autonomous Racing League!

Picture: Team FlyBy / TU Wien

We’re excited to announce that team FlyBy snatched a silver medal in the second season of the Abu Dhabi Autonomous Racing League (A2RL)! The A2RL was held at The Unmanned Systems Exhibition and Conference (UMEX), which took place in Abu Dhabi in late January. Team FlyBy is a team of students from TU Wien and the robotics club robo4you.at.

At the A2RL races, small quadcopters navigate a course of racing gates as quickly as possible. Compared to many robotics competitions, the rules of A2RL are exceptionally strict and particularly fair: Every team uses an identical drone - hardware modifications are prohibited, so the competition revolves entirely around creating optimal software. This shifts the focus to what ultimately determines performance in autonomy: perception, state estimation, and control software that remain reliable under real-world constraints.

Before team FlyBy could participate in A2RL, it had to go through two rounds of qualification and a five-week training phase spanning October and November of last year. The team passed both rounds with flying colors and completed the first stage on the first day of testing, with time left to systematically improve their stack. That additional time proved extremely valuable: In October, the team’s drones were typically flying at about 2–3 m/s, but by the end of November, they were already pushing towards 17 m/s. This increase was not just a matter of increasing speed, but improving robustness across the entire pipeline, because faster flight reduces the margin for perception delays and state-estimation drift. With these improvements in both speed and robustness, Team FlyBy was ready to move beyond the qualification rounds and tackle the whole challenge of the race.

Perception and Timing Under Severe Constraints

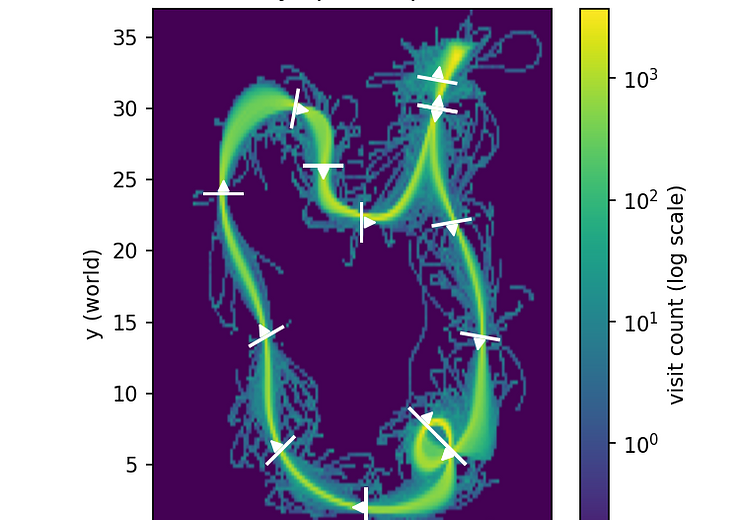

At the core of A2RL is a perception-and-control loop that must run reliably at high speed. The main perception task is detecting racing gates from the onboard camera in a way that remains stable across lighting changes, motion blur, and rolling-shutter artifacts. To address this, Team FlyBy trained a network to detect gates in the image stream and designed a filter that fuses these visual updates with IMU data. Their vision model ran onboard with a latency of roughly 5 ms per inference at a resolution of 820×616. The team operated the camera and processing pipeline at 120 fps, which is essential for keeping the delay between sensing and actuation small enough for high-speed flight. To reduce motion blur, the camera used an exposure time of only 3 ms. While this enables fast flight, it also introduces new challenges: the local 50 Hz power grid in Abu Dhabi can cause visible flicker from some lamps, which becomes noticeable in images captured with such short exposures. In practice, this adds another source of perception noise that must be handled by the gate detector and filter.

Precise timing and synchronization become increasingly crucial as the drones’ speed increases. To improve time alignment between camera frames, IMU messages, and estimator updates, Team FlyBy implemented custom extensions to the flight controller firmware, enabling improved synchronization and batching of IMU data. With this setup, the team was able to bridge gaps between reliable visual updates and achieve enhanced estimator stability in the fastest sections of the track. For control, the team used a model predictive control (MPC) approach throughout the qualification rounds, as it provides a structured way to track trajectories and allows systematic tuning as the vehicle dynamics and estimation characteristics become better understood. Over time, as the speed targets increased, team FlyBy reached a point where reliable tracking required increasingly careful tuning and where small state-estimation imperfections started to strongly affect the controller’s performance. As performance margins tightened, the team moved from simulation and practice runs to on-site testing in Abu Dhabi to finalize their setup for the finals.

Returning to Abu Dhabi: Final Preparations

Only six teams advanced past the qualification rounds for the final race in Abu Dhabi. After the second qualification round had ended in November, all teams worked to improve their systems, and overall performance levels had noticeably increased by the time the competition began. Team FlyBy also arrived with new ideas, though it was initially unclear whether these could be implemented in time or integrated into the software stack. A particular challenge arose in state estimation at higher speeds: as flight speeds increased, the system had to handle longer segments without strong visual corrections and became more sensitive to small inconsistencies between the real drone and the MPC model. After intensive development and repeated verification, the team successfully deployed a new state-estimation approach during the first days of the week. The improvement in consistency and stability was immediately evident in both internal metrics and live tracking. However, this advancement shifted the bottleneck to the controller, which now needed to follow significantly more aggressive trajectories without compromising stability.

In practice, pushing the MPC controller to reliably track the faster trajectories proved to be significantly more difficult than expected. The controller displayed different failure modes depending on the desired speed and trajectory shape. With limited remaining on-site testing time, other strong teams—such as KAIST, which had demonstrated similar performance in the qualification—continued to increase their speed through persistent tuning. This underscored the need for an approach that could deliver improvements within days rather than weeks.

A Late Pivot to Reinforcement Learning

During December, Team FlyBy began working on an experimental reinforcement learning (RL) controller originally intended for the next season, with the long-term goal of replacing the MPC. Because state estimation had become the primary focus in the weeks leading up to the event, the team had little opportunity to test RL on real hardware, and the controller was not yet integrated into the onboard software stack. Transitioning from a controller that could fly in simulation to a trained agent capable of operating in the real world under completely different constraints remained a significant challenge. An opportunity arose when the racing gates were moved from the testing location to the UMEX event track at ADNEC, leaving the team with a weekend without test time. This period was used to continue development and train the first promising policies.

The reinforcement learning workflow consists of two distinct stages: First, policies are trained offline in a simplified environment to obtain the neural network weights. This lightweight setup allows for rapid iteration and parallel execution of many rollouts on the GPU. Second, the trained weights are loaded into an inference node within the software stack, which runs either on the real drone or in a more realistic simulation. The inference node receives observations from the state-estimation pipeline, processes them through the policy network to produce actions, and sends those actions to the flight controller. Initially, these two stages did not align: Policies that performed well during training became unstable when deployed through the inference node using estimator-generated observations, repeatedly failing around the fourth gate in both realistic simulation and on the real drone. The issue was traced to a bug in the production inference node, where part of the observation was constructed incorrectly. After fixing this observation bug, the same trained weights immediately produced stable behavior during deployment.

First Stable Runs and Policy Iteration

With the bug fixed, Team FlyBy used a testing slot, around 2 a.m., to validate the updated controller. The drone immediately completed three laps before being manually stopped, maintaining a stable target speed of approximately 12 m/s across the full track. Beyond the raw speed, the most significant outcome was that the RL policy remained stable on track segments where the MPC had previously struggled with trajectory tracking, and it appeared more robust to state corrections following longer stretches without visual updates. This stability enabled systematic policy iteration. At that point, the team’s best MPC lap time was 9.4 seconds, while the first stable 12 m/s RL policy recorded a lap time of around 11 seconds. The focus then shifted to training faster policies while preserving enough robustness to complete laps consistently.

Tuesday was the last full day for Team FlyBy to test and select policies before the competition on Wednesday and Thursday. The team organized their agents into families based on training parameters and intended speed targets, evaluating them not only by expected lap time but also by how accurately they tracked the racing line and how well their flight style aligned with what the state-estimation could support in the real environment. It became clear that speed alone did not determine performance: some policies learned more efficient racing lines and smoother gate approaches, reducing estimator stress and improving overall reliability. By the end of the day, the team had assembled a portfolio ranging from slower, safer policies to faster, riskier ones that occasionally crashed during aggressive maneuvers near gate corners. One RL agent achieved a lap time of 8.6 seconds, already nearly a second faster than the MPC baseline. Each agent typically required about 25 minutes before it became clear whether it had learned a viable racing line. After roughly 40 minutes, the first promising fast runs could be observed in simulation, and after about 1.5 hours of training, a policy was generally ready for real-world deployment. Slower policies were trained on an RTX 4070 laptop GPU, while faster policies requiring longer training were run on an RTX 4090 at a remote cluster. from robo4you.

Speed Racing

On Wednesday, “speed racing” began. This time-trial discipline of A2RL requires each team to fly two continuous laps as fast as possible. Team FlyBy first deployed their safer 12 m/s policy to secure a clean time and appear on the leaderboard, then continued with faster agents. During these runs, they achieved an 8.0-second lap with a policy reaching around 17 m/s, providing a strong foundation for the multi-drone competition. The qualifying round placed Team FlyBy in the Silver group (teams 4–6) alongside KAIST and CVAR UPM, both of which were using MPC. KAIST had demonstrated faster lap times but experienced frequent crashes, while CVAR, though slower, was remarkably consistent and collected points reliably—a decisive factor in group-based scoring.

Team FlyBy began the races with a stable RL policy, prioritizing collision-free finishes and predictable behavior while racing alongside other drones. Across the first five races, the team collected 15 out of 25 points, finishing first three times. In one race, a collision with another drone eliminated the competitor, yet the RL policy continued, and the state estimation remained stable even after the impact. As the competition progressed, it became evident that KAIST was steadily improving and that Team FlyBy’s lead, while strong, was not entirely secure. The team deployed a newly trained, higher-speed policy that had shown excellent metrics during training. With only a few minutes between races, there was no opportunity for manual simulator validation, so the team relied on automatic evaluation results from the training pipeline. The estimated lap time was 7.3 seconds, with peak speeds near 20 m/s on the straights. Based on prior experience, real-world lap times are typically 300–500 ms slower than simulation estimates, but even accounting for this, the policy was expected to be significantly faster than any previous deployment.

In A2RL, the start signal is indicated by beeps, but the actual “go” depends on human reaction time. After several days of little sleep, Team FlyBy had struggled with consistent starts. This time, however, the team launched almost simultaneously and passed the first gate narrowly ahead. Over the first lap, they built a lead, and during a complex maneuver near the end, KAIST crashed and could not recover. CVAR remained in the race, applying pressure through consistency, but Team FlyBy’s policy flew the remainder of the race cleanly, recording a lap time of 7.8 seconds. This not only beat the MPC baseline by nearly two seconds but also set a new personal record. With this result, their point lead became large enough to secure first place in the Silver group. After months of development, two qualification stages, and an intense final week of testing, integration, and training, the race concluded with a result that reflected the team’s sustained effort and software development.

A heartfelt thanks to Radu Grosu, Michael Stifter, the robotics club robo4you for their continuous support, guidance, and help throughout the project, and the HTL Wiener Neustadt for letting team FlyBy make dry runs in their sports hall on weekends, which made a major difference during intensive development phases. Lastly, the team thanks Posedio for sponsoring and supporting their work.

Team members

Team FlyBy’s core members are:

- Joel Klimont (PhD student under Radu Grosu, head of the Research Unit Cyber-Physical Systems at TU Wien Informatics).

- Alexander Lampalzer (Master’s student @TU Wien)

- Jakob Buchsteiner (Master’s student @TU Wien).

The team was additionally supported by:

- Konstantin Lampalzer (Master’s student @TU Wien)

- Thisas Ranhiru (Bachelor’s student @RIT Dubai)

- Akos Papp (student at HTL Wiener Neustadt and member of robo4you).

Curious about our other news? Subscribe to our news feed, calendar, or newsletter, or follow us on social media.