Heinz Zemanek and the Curious Story of the “Mailüfterl”

Indelibly linked with TU Wien, Heinz Zemanek’s intellectual and personal heritage is a beacon of excellence—and wit—in our history.

Picture: TU Wien Archive / Heinz Zemanek Estate

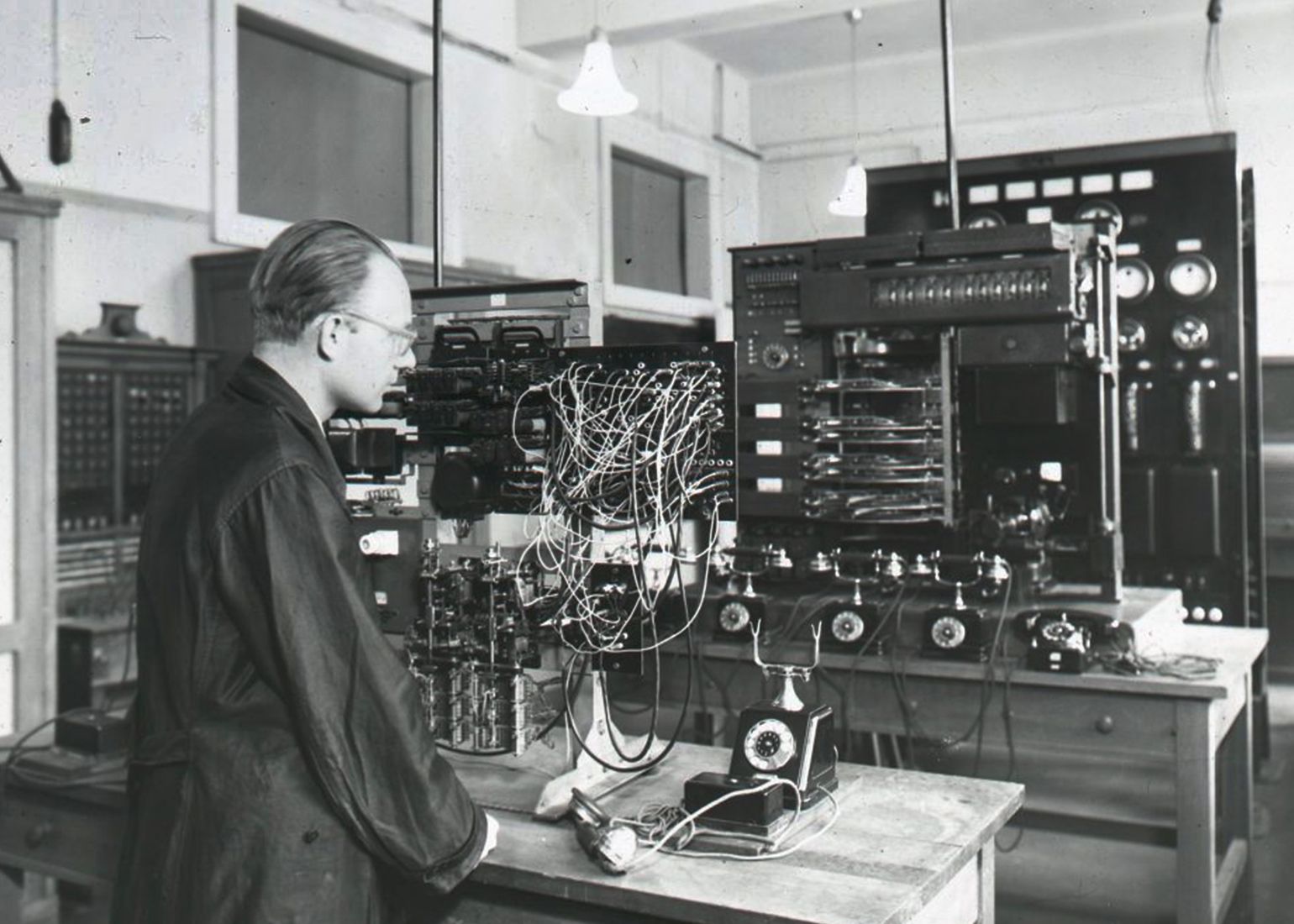

When, after two years of construction, a “semi-legally built” machine received the final touch-ups in 1958, its engineer, the Austrian computer pioneer Heinz Zemanek (1920-2014), quickly came up with a name that, even today, computer scientists and engineers recognize all over the world: Mailüfterl, literally “May breeze.” In allusion to the American vacuum tube computers of the time, which bore names such as “Taifun” or “Whirlwind,” Zemanek thought that the Vienna computer would not reach their speed, but “it would be enough for a May breeze.”

Zemanek later confessed with a wink that it had been a semi-illegal undertaking because they were just group of students and a “small university assistant” who did not have an official permission to build the computer, and thus were left without any financial or legal support from the university.

In terms of speed to cost ratio, the Mailüfterl was somewhere ahead of ERMETH in Switzerland and the Z22 in Germany, but behind the American IBM 650.

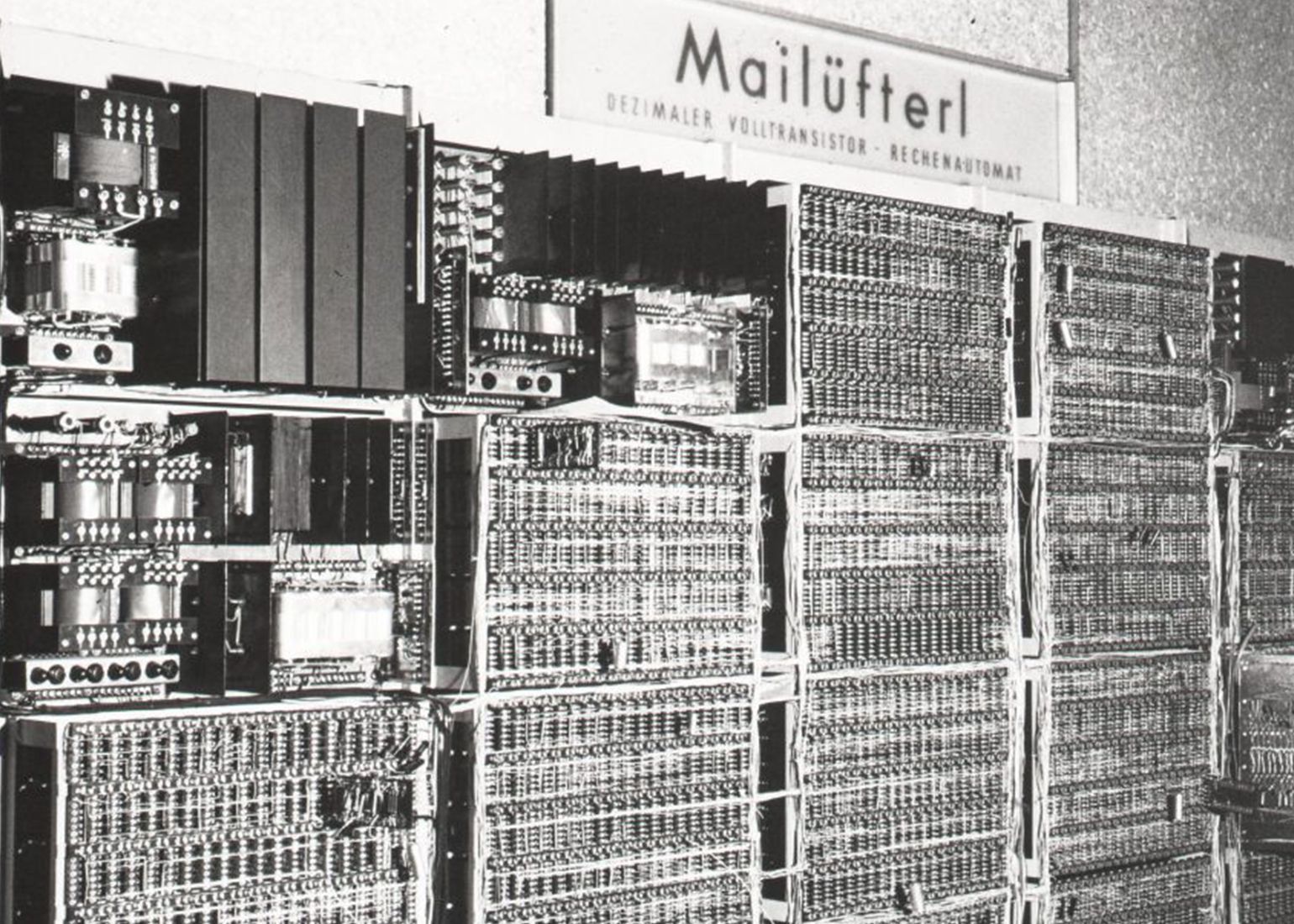

Move Aside, Tubes. The Transistors are Coming.

As one of the first computers worldwide, the Mailüfterl did not work with electron tubes, but with transistors. “Replacing electron tubes with transistors was an essential step in the miniaturization of electronics,” says Richard Eier, a student in Heinz Zemanek’s team. “This miniaturization has continued ever since and enables the computer performance we use every day today.”

Picture: TU Wien Archive / Heinz Zemanek Estate

What’s good enough for hearing aids, is good enough for Mailüfterl

The Mailüfterl was not only smaller than it’s tube-based cousins; it also required much less power and therefore did not need air conditioning. Yet getting enough transistors to build a flexibly programmable computer at an affordable price was not easy at the time. Lucky as they were, the team received the necessary 3,000 transistors as a gift from the company Philips. The fact that these transistors were designed for the use in hearing aids sounds amusing—but they were nevertheless ideally suited for electronic circuits.

Music, Maths, and Phone Calls

After building the hardware, the team went to programming from 1958 to 1961. On 27 May 1958, the Mailüfterl calculated the prime number 5,073,548,261 in 66 minutes. In 1959 a music-theoretical program was developed for the twelve-tone composer Hanns Jelinek —after 60 hours of computing, Mailüfterl produced a result.

Picture: TU Wien Archive / Heinz Zemanek Estate

The Mailüfterl was freely programmable and, therefore, extremely flexible. The engineers used it for simple mathematical operations, such as the already mentioned calculation of prime numbers. But more unique algorithms ran on the Mailüfterl as well. “It was coupled to a frequency generator to play twelve-tone rows calculated by the computer,” recalls Richard Eier. “As soon as it sounded halfway harmonic, you knew you had made a mistake.”

And since the engineers didn’t want to sit idly next to the machine while it computed its tasks away for hours and days, they connected the main accumulator of the Mailüfterl to the telephone: They regularly called from home to determine from the audible “melody” if the program was still running.

1961: Big Blue Takes Interest

At that time, it was unusual for universities to deal with computer technology in such a practical way; instead, it was private companies that developed computers. So it is not surprising that IBM quickly became aware of the Mailüfterl: In 1961, the company bought it and offered Zemanek to set up a dedicated lab for him, the IBM Laboratory Vienna. Not long after, he and his team, together with Mailüfterl, finally moved. IBM took over essential parts of the technology for the 360 machine, which was very successful from 1964.

At IBM, the Mailüfterl was used for a few more years until it was finally no longer functional in 1965. After the computer was taken out of service by IBM in 1966, it went to the JKU Linz. Since 1973, you can see the original Mailüfterl at the permanent exhibition of the Technical Museum in Vienna. The smartphones with which visitors photograph it nowadays surpass it in computing power. But the scientific and historical significance of the first sizable Viennese computer cannot be denied, and even Google honored it with a documentary short film in 2013.

Heinz Zemanek

Picture: APA

Engineer, Teacher, Enthusiast

Heinz Zemanek (1920-2014) studied at TU Wien and graduated in 1944 with the thesis, “On the generation of short pulses from a sine wave.” Between 1947 and 1961, he worked at TU Wien, where, in 1950, he received his doctorate, and in 1958 his habilitation.

I am an engineer at heart, and that means: True is what works.

“Heinz Zemanek was an incredibly motivating person,” said Richard Eier, who wrote his diploma thesis with Heinz Zemanek in the 1950s. “He was not only an outstanding scientist but also an important patron for generations of students to whom he passed on his enthusiasm for computer technology.”

At his IBM lab, he later concentrated mainly on programming languages. The “Vienna Definition Language” (VDL) and the “Vienna Development Method” gained international importance in the 1970s. In 1976, Zemanek was appointed an IBM Fellow by the then computer giant and thus had the opportunity to choose his tasks entirely freely. In 1964 Zemanek was appointed associate professor at the TU Wien, and in 1983 he was appointed full professor. In the mid-1980s, Zemanek retired—but only formally. He retained his enthusiasm for research and teaching until old age. His scientific oeuvre consists of around 500 essays and seven books, including “Computers, World Power” (1991) and “From the Mailüfterl to the Internet” (2001).

In 2013, Heinz Zemanek returned yet again to his alma mater when he attended the inauguration of our Vienna Gödel Lecture series, held by one of the most influential pioneers in Computer Science history, Donald E. Knuth, Turing Award winner—and a longstanding friend and colleague of Heinz’.

Awards and honors

Zemanek was the founding president of the Austrian Computer Society, which since 1985, awards the “Heinz Zemanek Award”. He served as the president of the International Federation for Information Processing (1971-1974) and was a member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. He was a corresponding member of the Royal Spanish Academy of Sciences, an honorary member of the Vienna Society for the History of Technology, corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and a full member of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Picture: TU Wien

On 25 February 2000, TU Wien Informatics named the historic lecture hall in its main building in Favoritenstraße 9-11 “Heinz Zemanek-Saal”.

Heinz Zemanek received numerous awards and accolades, amongst others the Cardinal Innitzer Prize, the Grand Decoration of Merit of the Republic of Austria, the Leonardo Da Vinci Medal of the European Society for the Education of Engineers, TU Wien’s Prechtl Medal, the Kompfner Medal of the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology, the Golden Decoration of Honour for Services to the City of Vienna, the IEEE Computer Pioneer Medal, the Oscar von Miller Plaque in Bronze of the Deutsches Museum and the John von Neumann Medal of the Hungarian John von Neumann Society for Computer Science.